Today's reading.

Tradition says that the author of Genesis was Moses. Despite many modern attempts to dissect the text like a frog in ninth grade biology, I don't think there is much firm evidence to say that Moses wasn't the author. In fact, the end of the last chapter and this one together provides pretty good internal evidence that Moses had a hand in the writing of Genesis.

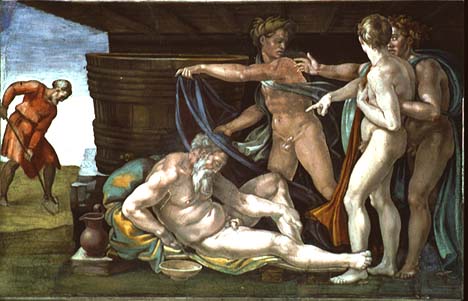

You'll recall that at the end of chapter 9, Noah loses himself at the bottom of a wine bottle. In that story, Ham, Noah's youngest son, finds his passed out, naked father and, rather than cover him up in dignity, goes and tells his brothers about it. His brothers do the right thing and cover Noah up, but when Noah comes to his senses and realizes that Ham left him in his shame on the floor of his tent, he pronounces a curse on Ham's son, Canaan (9:25-27).

Chapter 10 introduces a new section of Genesis with a genealogy of Noah's sons. But this genealogy isn't there to simply convey the facts. Genealogies aren't merely there to tell you about Japheth's family tree. In fact, this genealogy has very little to say about Japheth because Japheth plays a very minor role in God's purposes as they will be set forth in the Scriptures from now on. This genealogy is meant to convey an important historical and theological point. And that's where Moses comes in.

Genesis wasn't written in a cave, but was the first of the five books of the Law, the Torah, which make up the first five books of our Bible. Genesis was written at the time of Israel's exodus from the land of Egypt and was meant for that audience: former Egyptian slaves whom God had miraculously delivered and whom God was now leading to a land that he had promised to their ancestors. So, from the perspective of an Israelite living fourteen or fifteen centuries before Christ, Japheth's family line is unworthy of more than the four verses it gets. But Ham's line is very significant. Ham fathered both Egypt (whose descendants oppressed the Israelites) and Canaan (whose descendants were then living in the land that God had promised to give to Israel). In other words, Ham's family gets fifteen verses to Japheth's four because Israel wants to know their enemies. God was leading them to war against the Canaanites, so they'd better study their opponent as best they can before starting hostilities.

Ham was the father of a virtual "who's who" of Israel's enemies: Nineveh, Assyria, Egypt, Sidon, the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, Sodom, Gomorrah, Babel (Babylon), the Casluhim (from whom the Philistines came). Name an enemy of ancient Israel and odds are you can find their name here. Israel (Jacob) was a descendant of Shem (where we get the word "Semite"). Shem's descendants get ten verses. But the emphasis here is on Ham and his son Canaan's line.

Which is why I think it makes sense that Moses had a hand in writing this genealogy. He was getting ready to lead Israel to fight Canaan, and so wrote this with an eye toward educating his people about where they came from and where the people they were about to displace from the Promised Land originated. All the names of all those evil peoples would have struck a bit of terror and resolve in the hearts of the soon-to-be-warring Israelites. Moses was getting them ready for battle.

The incredible thing about the gospel is that the dividing wall of hostility between Jew and Gentile, holy people and profane, has been broken down in Christ (Eph. 2:13-16). God's people in the Old Testament had to keep themselves holy by attacking and avoiding those who were not Jewish. But in the New Testament, that national religious separation has been abolished.

Israel would have heard "enemy, enemy, enemy," when they came to Genesis 10 and read the names of all those hostile peoples. But in Christ, that hostility has been transformed to a call to love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us (Matt. 5:44). In the gospel, we hear that God so loved the world, not merely the nation of Israel (John 3:16). In God's kingdom, we have no enemies, only the call to suffer injustice at the hands of those who hate us. We have no enemies in Christ, only neighbors whom we are called to love (Matt. 22:39).

Whose name makes your blood boil? Who are you inclined to dislike, even to hate? Who in your life do you consider an enemy? At his arrest, Jesus told Peter to put down his sword (John 18:10); you and I are likewise called, not to seek justice or vengeance for ourselves in this life, but to humbly submit ourselves to the law of love. We are to love those who hate us, to love those we want to hate. That is the beauty—and the responsibility—of the gospel.

No comments:

Post a Comment